Why Seattle’s NR zones are not going to achieve maximum allowed density.

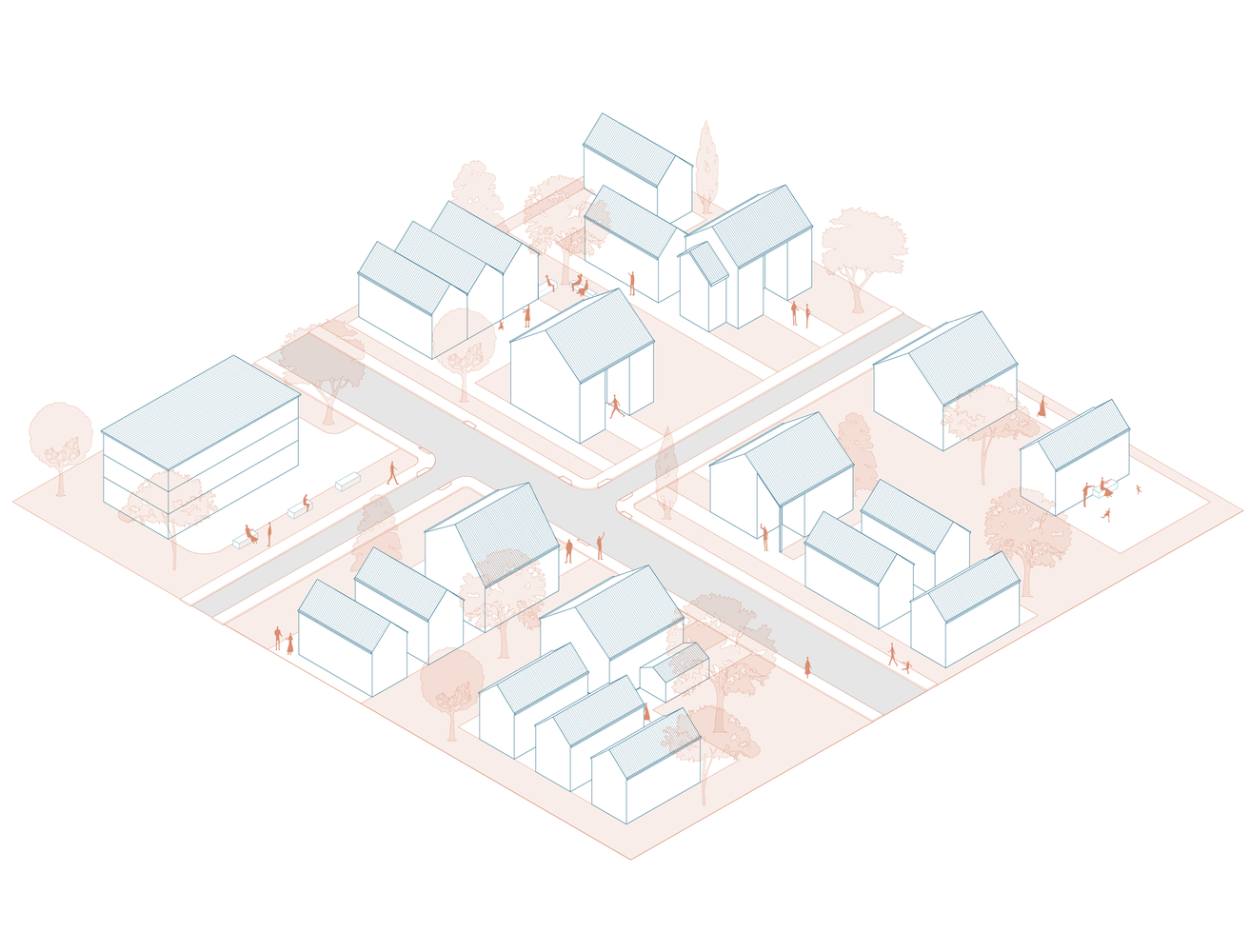

Earlier this year, Seattle enacted missing middle housing reform to allow greater density in NR zones. This was a much-needed reform as over 75% of the land that allows for residential uses in Seattle was zoned for single family use only. As our city grew, that restriction forced most new housing into a small portion of the city, driving up land costs, inflating home prices, and deepening the wealth inequality already embedded in our urban fabric.

At Fivedot, we strongly supported this reform. We know the racist history of single-family zoning and we looked forward to helping Seattle add density in a thoughtful, design-forward, and community-minded way.

But as we’ve begun working on projects under the new rules, a pattern is emerging: many of these sites will never reach their full allowable density. The reason is one of Seattle’s hidden costs of development—required street improvements.

When most people think about what makes housing expensive, they think of land, labor, and materials. Experienced builders might also mention time and financing costs.

Almost no one thinks about the additional costs imposed by the City to upgrade public infrastructure.

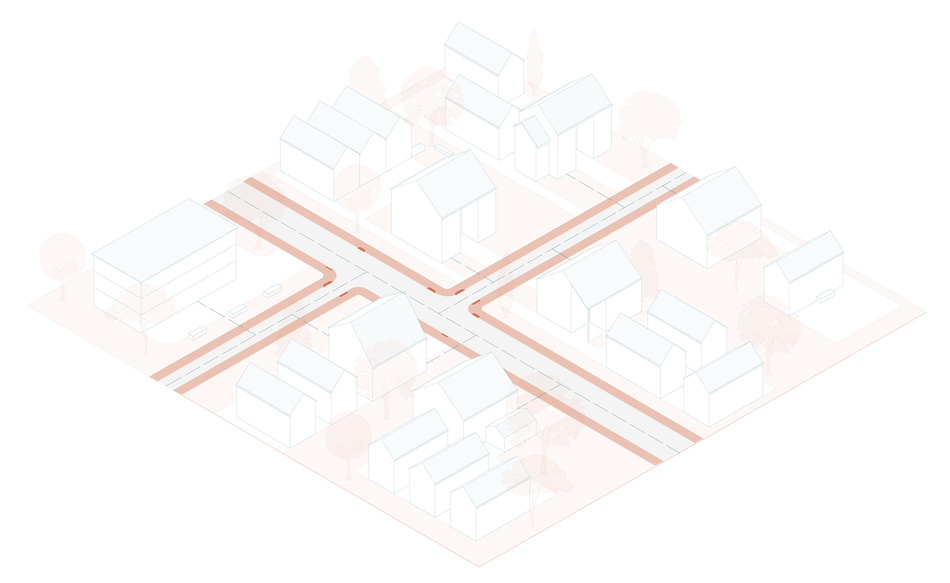

Seattle’s residential streets, sidewalks, storm lines, and other utilities were designed for single-family density and some of the utilities are already overburdened or under built. As we add housing, there’s no question that infrastructure will need upgrades. The question is: who should pay for them?

Right now, those costs are assigned directly to the property owner or developer adding units. On paper, that seems fair: they stand to profit, so they should pay. In practice, though, the scope of the required improvements often has little relationship to the scale of the project.

A homeowner adding two single family homes might be required to install hundreds of feet of new sidewalk, extend a stormwater main, or plant multiple new street trees. These upgrades benefit the entire neighborhood—not just the new units—but the private owner foots the full bill. While this arrangement helps the City expand capacity without raising taxes, it has a serious unintended consequence: it discourages the very density we just legalized.

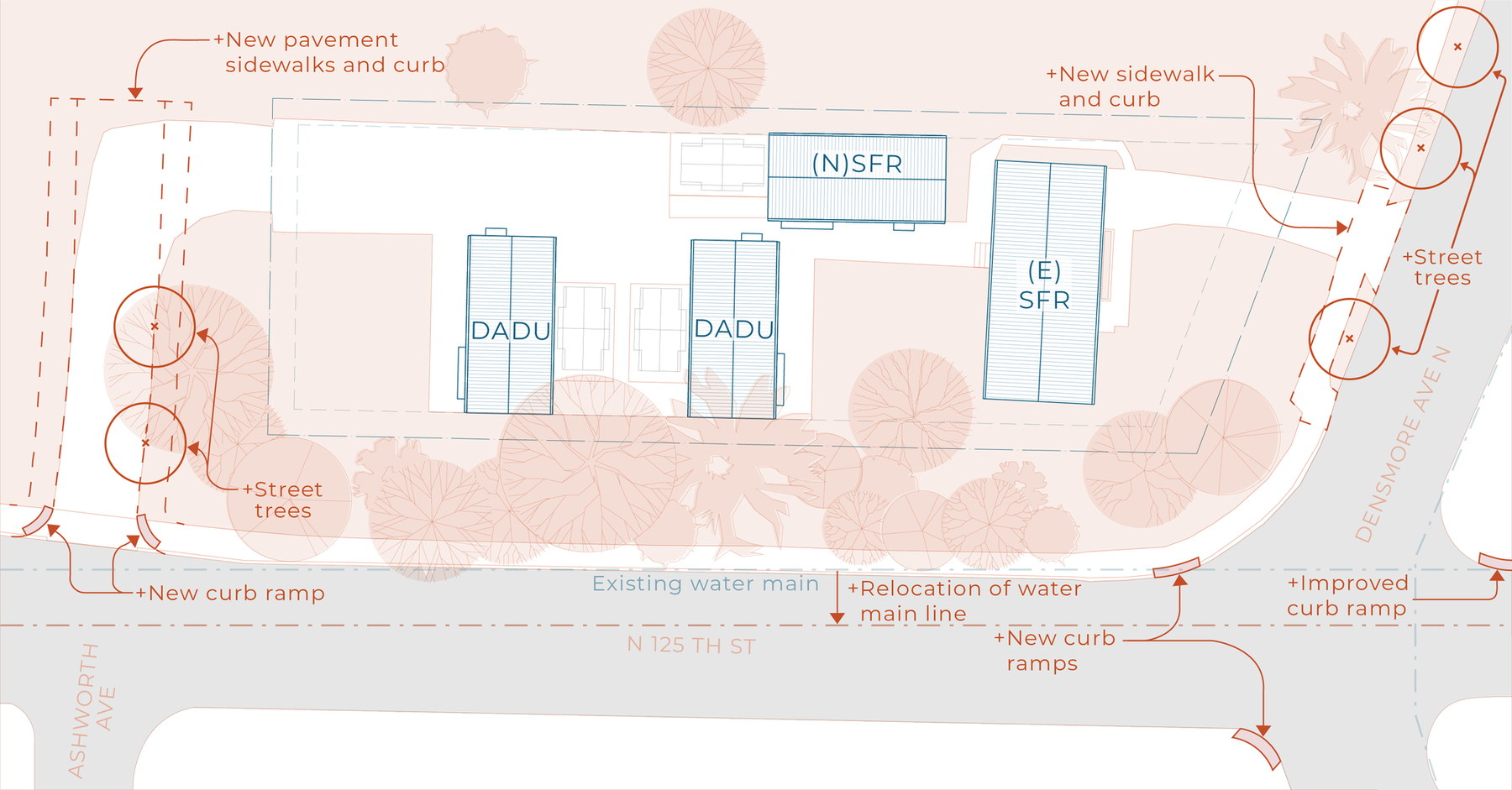

For a clear example of this we can look at a project we are working on right now.

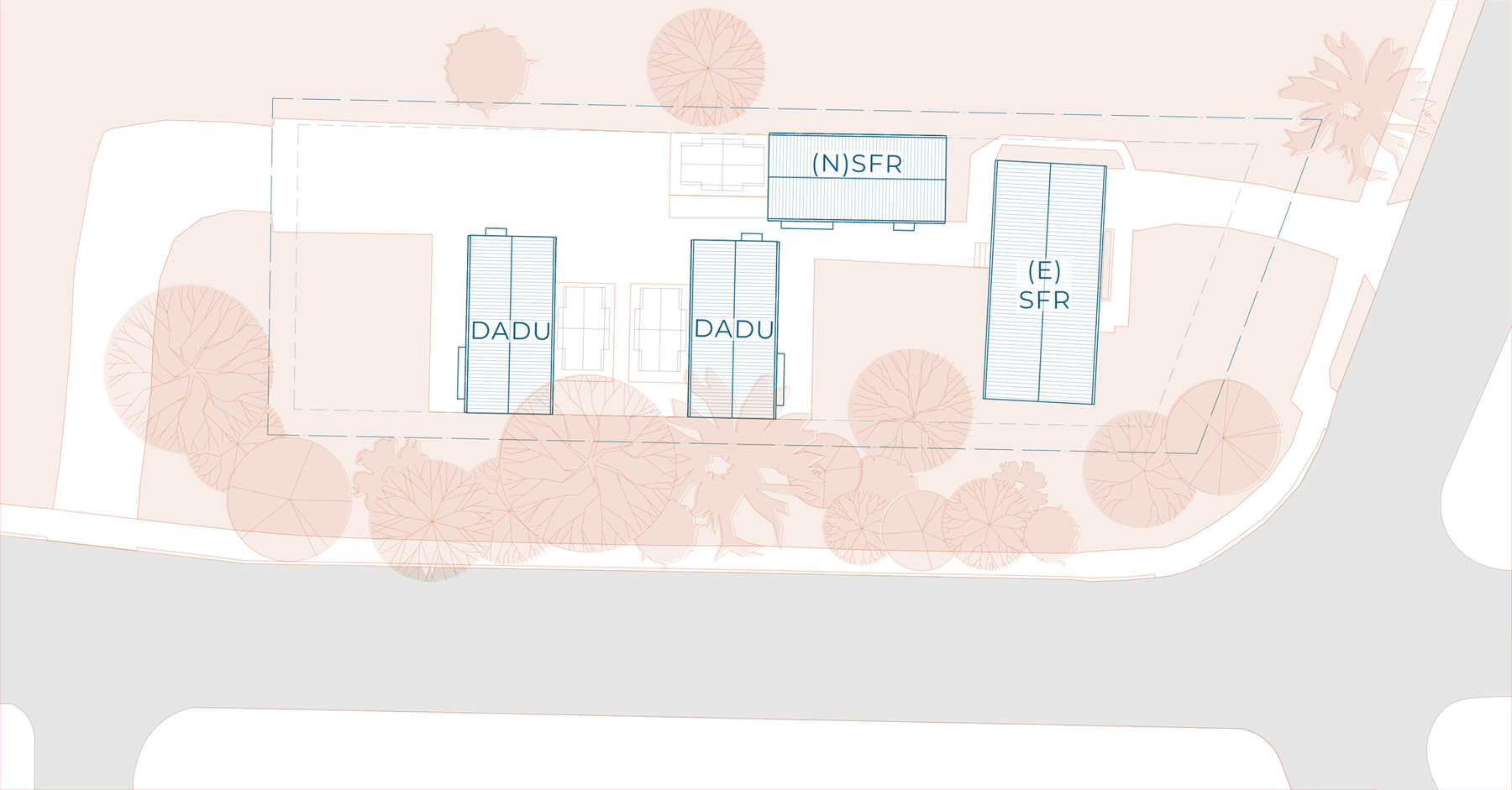

The property is ideal for infill—on an arterial, near transit, and large enough for six units. But because it’s 0.26 miles from a frequent transit stop (just 0.01 miles too far to qualify for additional units), the limit drops to four.

That was acceptable to our client—until the street improvements came into play.

They were told they would need to:

• Build 100+ feet of new sidewalk

• Install multiple new curb ramps

• Pave a part of the street

• Plant new street trees

• Relocate a water main

Estimated cost: $250,000, not including potential electrical upgrades to the nearest transformer— cost unknown until permit issuance.

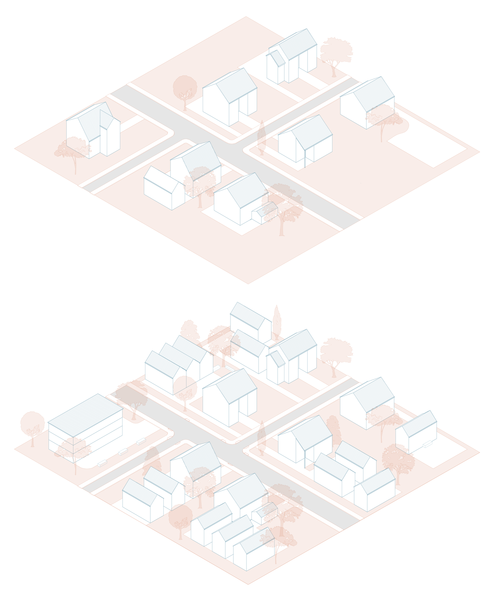

Faced with that, our client revised the project. Instead of four units, they’ll build only two DADUs. Because they removed the new single-family structure, no street improvements are required.

The result: one fewer family-sized home, and one more example of policy undermining its own goals.

This is not an isolated case. We expect to see similar choices made across Seattle as small developers and homeowners scale back projects to avoid infrastructure costs. We absolutely agree that Seattle’s systems—stormwater, sidewalks, and utilities—need investment to support new housing. But as long as we depend on private actors to deliver that housing, we have to make it financially viable. Whether the private market is the proper way to address the housing crisis is another discussion altogether.

Transferring the cost of public infrastructure onto small-scale projects might appear fiscally responsible in the short term, but in practice, it ensures we’ll fall short of our housing and climate goals. If we want the Missing Middle reforms to succeed, we need a public conversation about how we fund the public realm.

Evolving the Schooner: Adapting to New DADU Opportunities

Knowing that many homeowners will turn to DADUs as a practical path toward adding density under the new rules, we took the opportunity to revisit our pre-approved Schooner DADU design. As Seattle moves toward adopting the permanent legislation associated with HB 1110, several key updates to DADU regulations create new possibilities—and we wanted to make sure our designs take full advantage of them.

- Height – DADU height is no longer tied to lot width, but instead to the base zone height limit. In NR zones, that means up to 32 feet, plus an additional 5 feet for a pitched roof. For the Schooner, this change offers greater flexibility in how the first floor relates to exterior grade. We explored adding a third story, but the stair required would reduce floorplate efficiency to the point where the trade-off didn’t make sense.

- Size – A recent amendment to the permanent legislation allows DADUs to increase in size from 1,000 sq ft to 1,200 sq ft if they include three bedrooms. We’re developing a new version of the Schooner (called the Pint) that incorporates a third bedroom and bathroom to take advantage of this opportunity and to better serve growing families.

- Parking – While off-street parking is no longer required, many of our clients continue to request it. Our updated design includes an optional one-car garage, tucked neatly beneath the new third bedroom to preserve yard space and maintain the building’s compact footprint.

These updates reflect our ongoing effort to adapt thoughtful, well-designed solutions to an evolving code landscape—so that even within a challenging regulatory environment, we can continue helping homeowners and communities add meaningful, livable density to Seattle’s neighborhoods.

If you’re considering adding a DADU or want to learn more about how these changes might apply to your property, we’d love to talk. Reach out to us at [email protected]