How We Face the Street

A house in an urban or suburban setting is a blend of public and private experiences. It inevitably faces the street and communicates something through its façade and the space between itself and the public realm. Entering a home is not a binary shift but a layered transition—from the shared space of the street, through semi-public thresholds, into the private world within. The nature of that transition varies widely across cultures and geographies.

In parts of Latin America, homes often present a blank wall to the street—a threshold that conceals as much as it reveals. A simple doorway in this wall might lead to a lush courtyard or an ornate vestibule, creating an immediate yet abrupt shift from public to semi-private. In many European cities, this transition plays out vertically: street-level spaces may host guests or commerce, while upper floors remain private. In some Islamic architecture, ornate screens modulate the transition from public to private in thin planes.

In the United States, particularly in suburban developments, this transition is typically mediated by the front yard. Inspired by European estates, the front yard emerged as a symbol of domestic order and affluence—an open, manicured buffer between private dwelling and public street. Yet despite its cultural weight, the front yard is often underutilized. The real life of the household—gatherings, relaxation, children playing—typically occurs in the more private and enclosed rear yard. Residential architecture has reinforced this behavior: homes open to the back with large windows and sliding doors, merging indoor space with the backyard.

By contrast, the front yard remains visually open but socially closed—green space with little interaction. What if we reversed this model? What if we reimagined the front yard as a place for connection, the social heart of the home rather than a decorative buffer?

This question shaped one of our recent projects. Our clients, drawn to their neighborhood for its sense of community, wanted their home to foster connection—to turn a welcoming face toward the street and to create spaces for gathering not behind but in front of the house. Rather than hiding social life in the back, they asked us to bring it forward.

This has echoes of Latin American or Spanish architecture where a courtyard would be the first thing a visitor experienced of the home, perhaps before moving through that courtyard to a more intimate space. The American model would be the front porch although in this case we were tasked with making that transitional space larger and more layered in function and form.

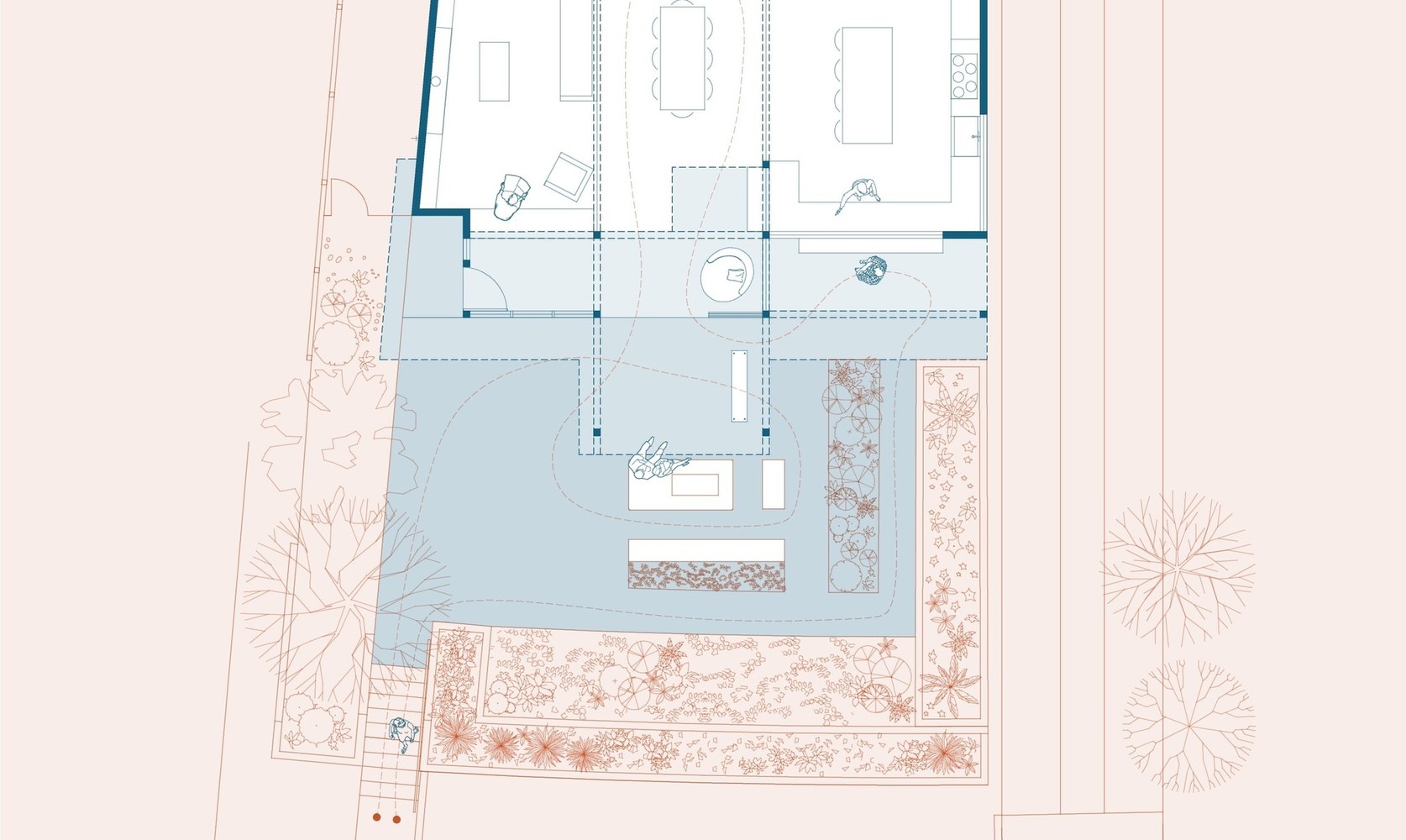

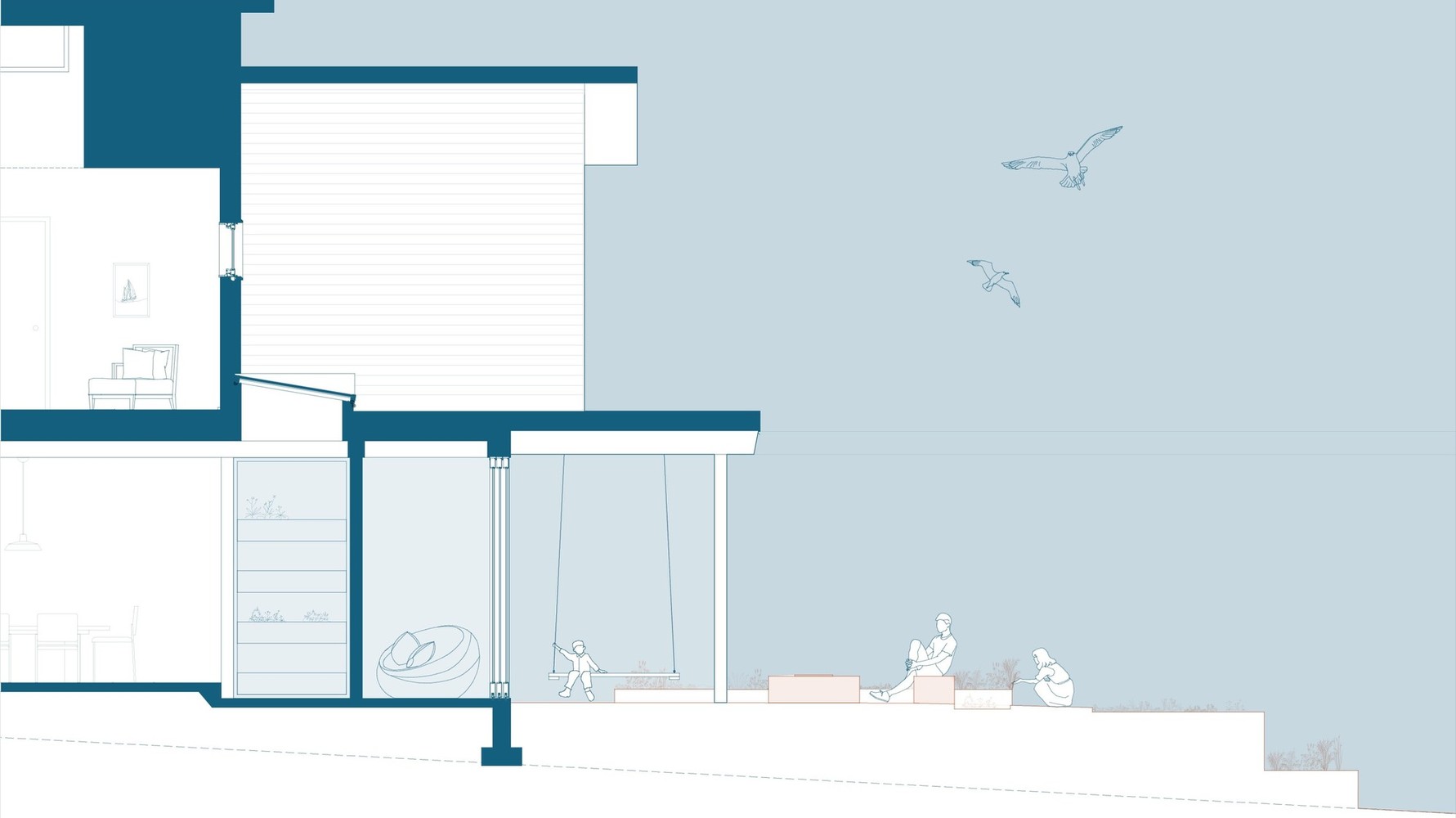

The site itself helped define the strategy. The house sits about five feet above street level, creating a soft separation while maintaining visibility. A low, planted retaining wall is interrupted by a short stair that leads up to a front patio furnished with built-in benches and a covered firepit. This outdoor “living room” invites interaction: neighbors stop to chat, friends gather for tea, and the family often relaxes here together. An overhead infrared heater extends seasonal use, while a continuous wood soffit—spanning both the patio and the interior entry—visually and materially connects inside and out. A large folding glass wall allows the indoor foyer to open completely to the front yard, creating a flexible threshold space that changes with the weather.

A skylight above the entry floods the space with natural light and nourishes a vertical planted wall below, emphasizing the continuity between interior and landscape. From the entry, one moves into the semi-private heart of the home—kitchen, dining, and living areas—which in turn lead to more private zones: a workshop, guest suite, and an upper-level bedroom wing.

This design flips the conventional model, but it also challenges broader zoning assumptions. Across many cities, mandatory front yard setbacks push houses deep into their lots, resulting in large but unused green spaces and thinning the urban fabric. These setbacks discourage density, interaction, and the layered transitions that make streets vibrant.

Seattle is now reconsidering this model. New zoning proposals aim to reduce required setbacks in Neighborhood Residential zones, opening the door for denser, more engaged development. We welcome this shift—not just for the opportunity it brings to build more housing, but for the chance to rethink how we relate to the street, our neighbors, and our shared public life.